“He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.”

“For the mind is its own place, and can make a hell of heaven, or a heaven of hell.”

- Milton (Paradise Lost)

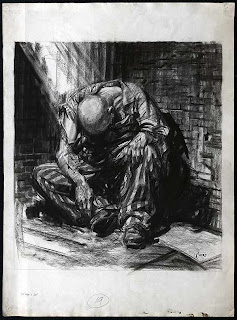

The process of adapting to prison life, or prisonization, has been described as exerting a dehumanizing effect that may result in feelings of hopelessness and alienation.[i] The psychological effects of prison are believed to vary according to the individual. However, it is within the context of imposed institutionalization that the inmate is vulnerable to the development of harmful attitudes such as a negative self-concept, devaluation of life and other generally destructive cognitions. It might be hypothesized that inmates serving life sentences (“lifers”) spend the longest time in prison, and would therefore undergo the greatest degree of prisonization. Whether the life sentence results in an attitude characterized by nihilism or adaptation is unknown at present; however, one could speculate that an individual’s pre-incarceration coping skills and overall constitution play a role.

Persons serving true life sentences (life without the possibility of parole) are a group of individuals living under a unique set of circumstances. Lifers must somehow adapt to the reality that there will be no future release date to sustain hope or a sense of purpose. Because they have been subject to an extreme form of permanent social exclusion, one might speculate that they would have an increased degree of hostility, mistrust, and nihilistic attitudes. However, correctional staff can attest to the fact that this is not always the case. Lifers often have the regard of their fellow inmates, and may be respected for having met the challenge of surviving in prison. Veteran correctional authorities note that some lifers “seem to mature into acceptance of their situation. Many take on a leadership role, setting a positive example…for other inmates.”[i]

To be sure, lifers are also in a position to use prestige and a “nothing to lose” attitude to control and/or manipulate other inmates in less than helpful ways. I will not be so naïve as to ignore my experience that some true lifers with nothing to lose may act as so-called “shot-callers” of inmate gangs. The existence of organized crime in corrections is an unsettled and unsettling dilemma. In fact, U.S. attorneys have had to prosecute leaders and members of highly sophisticated organized crime syndicates operating out of the nation’s prisons. Aryan Brotherhood gang members have been convicted of running an extensive criminal enterprise from behind bars that involved murder, narcotics trafficking and conspiracy in an effort to rule the nation's prisons.[ii] In some worst case scenarios, incarcerated gang leaders have ordered the murders of individuals living in the community. In a study of offending during incarceration, it was found that 40% of inmates were “chronic or extreme career offenders even while incarcerated.”[iii] Further, a small cadre of inmates accounted for 100% of the murders, and 75% of the rapes in prison.

These individuals, by and large, would appear to be fundamentally different from the rest of the prison population. Sure, there will be some overlap. But in general they are different – different from inmates with severe mental illness, and different from non-mentally ill inmates who have a desire to rehabilitate themselves. Further, their impact on the correctional environment, and what is left of rehabilitation, can be substantially damaging. Besides creating a climate of fear which undermines rehabilitative efforts, there is the issue of abusing vulnerable, mentally ill inmates. Psychiatric hospitalizations may be directly precipitated by such abuse. Other very sad cases involve impressionable or otherwise vulnerable mentally ill inmates being “recruited” into gangs so that they might serve as pawns for a gang’s strategic maneuvering. I could go on, but you get the point – these are drastically different populations of individuals, and it is not clear that intermingling them serves a legitimate penological interest, ethical or humanitarian interest.

But let me assure that there are, in fact, a good many lifers with a more pro-social, positive disposition. Little is known about the psychological structure or psychiatric morbidity of lifers from a research standpoint. Even less is known about effective treatment or programming approaches to lifers who struggle emotionally and are otherwise unsuccessful in finding purpose to their “new life” in prison. Why one lifer chooses a more positive path and another a more negative one is interesting to consider. My primary interest in lifers has stemmed from personal observations that life meaning and/or purpose in life appears to influence inmates’ coping styles and, in some cases, their risk of suicide. This interest next led me to the writings of Viktor Frankl who was the first psychiatrist to emphasize the importance of studying meaning in life within a psychological context.[iv] Frankl’s experience as a Nazi concentration camp prisoner led him to conclude that a primary motivation for humans is a “will to meaning,” or a drive to find meaning and purpose in life. A failure to find meaning and purpose may result in feelings of hopelessness, suicidality[v] and other self-defeating actions.

Based on the work of Frankl, the Purpose-in-Life (PIL) Test was constructed to assess or quantify the construct of meaning in life.[vi] Surprisingly, there is little research on this subject as it relates to prison inmates. What research does exist was done primarily in the 1970’s, and much about the correctional landscape has changed since. A 1973 study found that recidivists scored significantly lower on the PIL than did first sentence prisoners who, in turn, scored significantly lower than normal controls.[vii] In a 1977 study, inmates (who were not serving life sentences) were found to have scored significantly lower than normal subjects on meaning and purpose in life.[viii] Subsequent research has found an association between the development of substance abuse problems and a lack of purpose or meaning in life.[ix]

One might speculate that the current abandonment of rehabilitative programming in corrections has only served to further re-enforce the inmate’s diminished sense of self-worth and personal value. Ultimately, feelings of diminished personal worth lead to a questioning of purpose. I have observed that once an inmate reaches some individualized level of nihilism, he demonstrates a greatly reduced ability to participate in and benefit from rehabilitative and treatment efforts (ie., no meaning = no purpose or reason to change). In addition, when an inmate has strong nihilistic beliefs, there is often little motivation to self-regulate behavior.

These empirical observations of the adverse effects of nihilistic beliefs in inmates are consistent with research findings in non-incarcerated populations. For example, social rejection has been found to increase feelings of meaninglessness, and decrease self-awareness and the ability to self-regulate behavior,[x], [xi] and ultimately to suicide and/or self-destructive behaviors.[xii] This theory has been called the “escape theory” to denote the individual’s motivation to escape from aversive self-awareness. The “escape” theory may have relevance to the psychology of inmates, particularly where the inescapable structure and discipline of a prison reduces their ability to use prior maladaptive coping mechanisms to avoid aversive affect and self-awareness.

What Frankl called the “will to meaning” is a highly personal and individual endeavor. Achieving happiness through one’s life purpose often involves an outward focus – that is, it is “other” directed. Admittedly, prison life appears to do little to encourage outward focus, especially in terms of healthy social and societal alliance building. Yet it is precisely through such “other” directed engagement that the stagnating bonds of self-absorption can be loosened, and toxic feelings of societal “persecution” can be overcome. One may wonder if ignoring the opportunity to emphasize life meaning and “other” directed interests may simply foster some inmates’ tendency to go into a “behavioral deep freeze” where misbehavior is reduced during the prison term, only to reemerge in society after release.[xiii]

References

[i] Nietzsche F: The Portable Nietzsche (W. Kaufmann, Ed.). Maxim no. 12 in Twilight of the Idols, p. 468; New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1982.

[i] Stinchcomb J: Corrections: Past, present and future. American Correctional Association, 2005; Versa Press, East Peoria, IL.

[i] Bruton J: The Big House: Life Inside a Supermax Security Prison. 2004; pg. 157. Voyageur Press; Stillwater, MN.

[ii] Richards T.: Aryan Brotherhood Leaders Are Convicted in Murders. The New York Times, July 29, 2006.

[iii] DeLisi M.: Criminal Careers Behind Bars. Beh Sci Law 2003 21: 653-669.

[iv] Frankl V: Man’s Search for Meaning. 1959; Boston, MA. Beacon Press.

[v] Edwards M, Holden R: Coping, Meaning in Life, and Suicidal Manifestations: Examining Gender Differences. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 2001; 57(12): 1517-1534.

[vi] Crumbaugh J, Maholick L: Manual for Instructions for the Purpose-in-Life Test, 1969; Munster: Psychometric Affiliates.

[vii] Black W, Gregson R: Time perspective, purpose in life, extraversion and neuroticism in New Zealand prisoners. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 1973; 12:50-60.

[viii] Reker G: The Purpose-in-Life Test in an Inmate Population: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1977; 33(3): 688-693.

[ix] Waisberg J, Porter J: Purpose in life and outcome of treatment for alcohol dependence. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1994; 33: 49-63.

[x] Twenge J, Catanese K, Baumeister R: Social Exclusion and the Deconstructed State: Time Perception, Meaninglessness, Lethargy, Lack of Emotion, and Self-Awareness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2005; 85(3): 409-423.

[xi] Baumeister R, et al. Social Exclusion Impairs Self-Regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2005; 88(4): 589-604.

[xii] Baumeister R: Suicide as Escape From Self. Psychological Review, 1990; 97(1): 90-113.

[ii] Richards T.: Aryan Brotherhood Leaders Are Convicted in Murders. The New York Times, July 29, 2006.

[iii] DeLisi M.: Criminal Careers Behind Bars. Beh Sci Law 2003 21: 653-669.

[iv] Frankl V: Man’s Search for Meaning. 1959; Boston, MA. Beacon Press.

[v] Edwards M, Holden R: Coping, Meaning in Life, and Suicidal Manifestations: Examining Gender Differences. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 2001; 57(12): 1517-1534.

[vi] Crumbaugh J, Maholick L: Manual for Instructions for the Purpose-in-Life Test, 1969; Munster: Psychometric Affiliates.

[vii] Black W, Gregson R: Time perspective, purpose in life, extraversion and neuroticism in New Zealand prisoners. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 1973; 12:50-60.

[viii] Reker G: The Purpose-in-Life Test in an Inmate Population: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1977; 33(3): 688-693.

[ix] Waisberg J, Porter J: Purpose in life and outcome of treatment for alcohol dependence. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1994; 33: 49-63.

[x] Twenge J, Catanese K, Baumeister R: Social Exclusion and the Deconstructed State: Time Perception, Meaninglessness, Lethargy, Lack of Emotion, and Self-Awareness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2005; 85(3): 409-423.

[xi] Baumeister R, et al. Social Exclusion Impairs Self-Regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2005; 88(4): 589-604.

[xii] Baumeister R: Suicide as Escape From Self. Psychological Review, 1990; 97(1): 90-113.

[xiii] Bruton J: The Big House: Life Inside a Supermax Security Prison. 2004; pg. 157. Voyageur Press; Stillwater, MN.

Indeed, I think that a person with "nothing left to lose" would be the most destructive inside or outside a prison. They might not stay outside the prison system for long. Might they not be compared with a sociopathic personality?

ReplyDeleteI know it's extreme, but if there's little chance for rehabilitation or even control of behavior might not the death penalty be wise method (within guidelines) to manage these individuals behavior and reduce their potential damage to a already unstable system and outside society?

In an ideal world, would it also not be considered a positive reinforcement to encourage individuals who had not reached a certain nihilistic level and corresponding level of "miss-behavior" towards "life-meaning" and "other" directed programs?

Would it increase their coping skills while isolating them from the "nothing left to lose" mentality even if they were "lifers"?